The first 3 design journals were brought to you by Grant Rodiek. Today, we switch perspective to Michal Walczak, the lead developer for Portal Games on Cry Havoc.

It’s possible that the best thing about being a game designer is that with every project you get to learn something new. You can’t merely rely on fixed aspects of your work because it may happen that precisely these fixed elements will lead you nowhere. Believe me, well-trodden paths are as useful in the board gaming industry as road maps from the eighties.

So what did Battle for York teach me?

First and foremost: there is no algorithm, procedure, or method known to man that would infuse a mass of cardboard, wood, and staples with a bit of heart. You can search all you want, but Google knows nothing on the subject. Yet this is this bit of heart that makes a difference between a good game and an above-average game. Without it, you will never create a game that could become embedded in people’s memory. This bit of heart in the game needs to be fought for, and sometimes you just need to work it out. With every moment of working on the game, with every rejected idea, with every moment of testing, the game can gain its heart. Sometimes you’ll find it—by chance—in an inconspicuous idea, sometimes it will stand out as a brilliant solution, but the truth is that you need to remember about it even as you begin creating the game.

So we have this project called Battle for York. The game makes sense, you can play a battle, but put it on the shelf and it will drop off the face of the earth. The chances that the game sees the light of day and hits the table ever again are as low as a dead man’s pulse.

So let’s check off all the standard solutions: Maybe the factions should be asymmetrical? No. Varied mediocrity is still mediocrity.

Perhaps the map should be asymmetrical, then? Combined with asymmetric factions, this could yield a high replay value. No. Mediocrity is mediocrity, no matter how many times and from how many angles it is observed.

Maybe we can change the cards that drive the mechanic? Add some features? We can create new tactical options for the gamers to use with their chosen factions. Perhaps we should allow the factions to develop? Perhaps we should change the way the troops are deployed, speed up the gameplay, streamline the scoring system? No, no, and no. It’s still mediocrity. Not a bit of heart in it.

***

Yet it all takes time. Weeks turn into months, and the guys are already making jokes about what I do at Portal Games. I’m sitting over Battle for York. Week after week. I’m not working on it, just sitting over it. I’m going round in circles, the game is changing, but there is no course ahead. Still, more weeks go by.

But one thing should be noted here: Battle for York is a game that Portal had been lacking for years. Portal’s portfolio of “strategic area control games with negative interaction and plenty of tools to kick your friend’s ass” is strikingly empty. And I’m sitting over Battle for York, the game I’ve longed for all my life—as a gamer and as a designer; over a project so important to our publishing house—and nothing. Time goes by and the game still doesn’t have that “something”.

A pro-tip: learn to quickly identify a standstill at work and respond to it. I couldn’t do that back then. At some point, Ignacy initiated a serious conversation about how the game was developing. We talked for a while and I explained all the changes made until then: those I applied and those I backed out of. We discussed every modification that wasn’t a dead-end street. Features, tactics, cards and other components that now littered the box, useless. There could have been many outcomes of this conversation: Ignacy could have taken over the project, he could have assigned it to someone else, he could have accepted refined mediocrity, he could have abandoned it altogether.

Instead, he clearly explained to me again what I could do with the project, what I could change or throw out. And there were many things I could alter: essentially the entire game, with the single exception of the battle board.

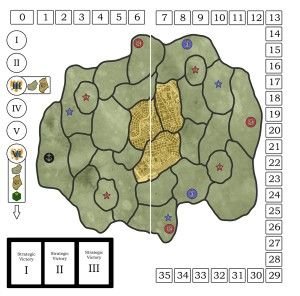

“Michal, for this board alone, I bought the rights to this game.” he pointed at battle board.

So I’m sitting there staring at the inconspicuously looking board. True, it works outstandingly well during gameplay. It really is a cool idea to resolve battles this way—that is, in waves. Every tactic used in the game effectively comes down to affecting the situation on this board. What about the rest of the game? What about the other 90% of the game’s mechanic? We just toss it overboard for now. You’ll look into rest later. Now focus on battle board.

In case you didn’t know what just happened: By throwing out 90% of the mechanic, Ignacy gave the game a fair-sized chunk of its left ventricle, along with a few inches of a protruding aorta. It took me a while to latch onto that, but the truth is that Battle for York was—just like any other project—a constellation of various fragments, more or less autonomous and of varying importance. The mechanic was never bad and maybe I’m a bit too harsh when I call it mediocre. Actually, to give you a better picture I can even say that most of it was cast in gold. But sometimes you just have to kick out some golden parts to make room for diamonds. For Ignacy, the game’s true gem was the battle board. It was because of this element that we worked on this game.

***

So I took the battle board out of the box. For the time being I put all the rest on the shelf.

If you want to know what it means to work on a project with only a few constraints, the first thing you need to understand is that every project is a Great Opportunity. And if you’re passionate about designing games, this is how you see it. It doesn’t matter if it’s a micro-game or a huge project with hundreds of components. So when Ignacy approaches you and says that the game is going to be published but it needs some polishing you know it’s the Great Opportunity. A chance to work on the game, gain experience, face the problems and deal with them. It’s your Great Opportunity to create an excellent game, one that will hit the tables worldwide, conquer the rankings, change the course of the board gaming industry. Because why shouldn’t it? It’s a Great Opportunity and nothing holds you back. Each project is a great dormant potential, from the first half-second of your work until the project goes to print. Every game is a Great Opportunity.

Any game designer passionate about his job knows this. And I know this, too.

And why is this Great Opportunity so important? Because you need to keep it in mind to improve the project with whatever best you have. You don’t hoard your best ideas to use them in one of your future projects, in one of the other chances, maybe in a game created solely by you—your original design. Nothing of the kind. You need to understand that as a designer, developer, test leader, or simply a tester, you must give your best. You don’t keep your best ideas for later. And it’s not about fighting the competitors in the market or increasing your sales. There’s something more to it. To be the best, the game needs to get the best from you. Otherwise, it’s just not going to work.

***

Once I was done with most of the previous mechanic, I gathered all the things I’d invented over the past years and tried to squeeze them into the game. The years of creating and remembering ideas—huge mechanics and minor features alike—bore fruit within a couple of weeks. All my dreams about board games, my demands, masterstrokes, and laborious considerations—all the best things I had—were soon loaded into this one game.

Imagine that a tactic your army can use is tied to a particular area. You’re fighting a battle for an important harbor, for a marine academy that will allow for more effective naval combat. Or you wage a battle for a fortress hidden among the hillsides because capturing it will help you train your troops in defensive tactics. Or think about extensive plains—if you command them, you can train cavalry and make it more effective in combat. Imagine that your faction behaves differently depending on the terrain you’ve conquered.

Or imagine that the game’s map is not merely flat—you can move through the tunnels and caves that riddle the entire area. Or maybe the actions you can perform will depend on the time of day—the planet you’re on rotates around its axis and while one side is enveloped in the dark, the other absorbs the scorching rays of the alien galaxy’s sun.

Hmm … What planet? What galaxy? What caves?

During these weeks, the game’s character changed somewhat. It turned out that Battle for York, originally set on an island in the Napoleonic era, had always been a sci-fi game in Ignacy’s mind. Do you know how difficult it is to change a game’s entire narrative? To transfer it to a different reality, to completely different technological surroundings? It may be disappointing but, in spite of appearances, when you begin working on the game this is just like a breeze. We gave our bayonet-wielding infantry space suits and better weapons, we turned the cavalry into machines, and cannons were now tanks. At this stage, the mechanic can forgive these things as it’s not too specific.

Battle for York sloughed its old skin and evolved into what was provisionally entitled Battle for Yrk. After all the changes the game now relied on worker placement, we could affect the planet by building various structures, we could learn new tactics and explore the planet. The game played quickly and was pretty intuitive, too. At this stage, this was no longer sitting over the project. When my rear end was in the chair, that was during rare moments of rest. For most of the time, I would run around the game cutting new components, writing down new rules, features, and tactics. Everything was still quite rough, but what began to emerge was promising.

***

Obviously, many of my splendid ideas turned out to be downright absurd. Many didn’t make their way to the final version of the game because they simply didn’t fit. Some others, however, fitted like a glove. It’s important to give the game everything you can, the best ideas you can come up with.

I did.

I don’t even know how and when, but suddenly we had the heart’s left atrium in the box. When I nudged it with a pencil, it rolled towards the left ventricle and stuck to it with a squelching sound. I had to present the project to Ignacy. We had to validate and verify it, then we’d think what to do next. One year had passed. Battle for Yrk had changed dramatically. I know that was when I was happy and could sleep soundly.

….to be continued.

Polski

Polski English

English Deutsch

Deutsch